Topics

00:09:59

The Fullness of Life

Video

Duration : 00:09:59

Never underestimate the power of this breath.

00:09:59

The Fullness of Life

Video

Duration : 00:09:59

Never underestimate the power of this breath.

People go—and they go, “I want to live in the moment called now.” And I’m like, “Noble thought! But you don’t even know what that is. You have no clue what is now.” Because it’s gone by the time you say “now.” It’s gone! It’s not there anymore. It’s—it’s gone!

And in fact, the reality is, the things are happening very fast—really fast: “Gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone!” And I, as a human being, I have no idea of the speed that this is going by—no idea. I’m like, “Oh, it’s okay; I’ll do it tomorrow.” Do you know how many “nows” will go by between now and tomorrow?

Somebody actually wrote me this question, “You know, people tell me you should think about tomorrow.” And she said, “People tell me to think about tomorrow, but I just want to be in the now.”

And I am like, “But what else can you do about tomorrow? Only think about it.” What else can you—but, by the way, what else can you do with tomorrow? You can imagine it; that’s all. Just think about it. Sit there and wonder what’s going to happen—if things will go your way or won’t go your way.

And you’re waiting for things to go your way. Aren’t you looking for the ultimate justice where everything will be put right? The only problem is you’re going to hit the wall before that happens. Because you have no idea how quickly that wall’s coming.

But, never underestimate the power of what’s keeping the two walls separated. Never underestimate the power of this breath.

Understand it, and you will understand what there is to understand about tomorrow, and what there is to understand about today, and what is there to understand about now—and what is there to remember about yesterday and what is there not to remember about yesterday. Because you’ve got to ride this moment called “now” to understand what now is about!

Think of it—think of it as this board, beautiful board—and they’re flying, whshew, whshew, whshew, whshew, whshew; you’ve got to catch one. And you’ve got to catch one, and you’ve got to get on it and ride it! And then you will understand. Then you will understand what now is all about.

It’s like, have you ever flown a kite? I have. And it’s a lot of fun. And logically it makes no sense whatsoever. It’s just a piece of paper or a cloth with bamboo in the case of paper or a fiberglass rod in terms of those big kites. And you have a string. And of course, you need the wind to fly it.

So you’ll get there in the field; you hold the string in your hand; the kite goes up, and you’re just looking at it. And it’s flying, and that’s a lot of fun. Does that make any sense? Because you could get somebody else to hold it and hold the string. And that guy can run out 300 feet and hold the kite, and you could just look at it. But that’s not any fun!

It flies in this wind, and you feel that power of that wind through that kite, through that string, in your hand. And to keep it up there you have to be with the game. Because when the wind starts to go down, you need to run backwards. And it goes back up, and the wind picks up, and now you can let it go, slowly, slowly, and you can get back to where you were.

It’s something about flying a kite; I don’t think anybody can explain to anyone why it’s so much fun. And it’s the same way, riding that board of the moment called now, of what it is like to get on it and go, go with that moment called now! And be there. And to ride—take that ride, and take that ride inside, not outside.

And all of a sudden, slowly everything starts to fall away; everything doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is the ride itself, the ride with the breath—to slide with this breath, like those waves in the ocean, this breath coming in, this mighty force that has been made so gentle, holding apart those two walls: “I exist. And I appreciate my existence.”

And it’s okay. I’m full! I’m not full because of some thing, but I have found the fullness of my clarity in me. I have taken that plunge and dove in—and loved, and know—I know I did not touch the bottom. And for as far as I could see, I saw clarity. There was no end.

And if that wasn’t enough, I’ve taken a dive in the ocean of kindness, and I did not touch the bottom; I didn’t even try. And I was overwhelmed by its vastness.

I am full because I have been shown the fullness of this life. This is what you should do too. I tell you this—I tell you this—because if I can do it, you can do it.

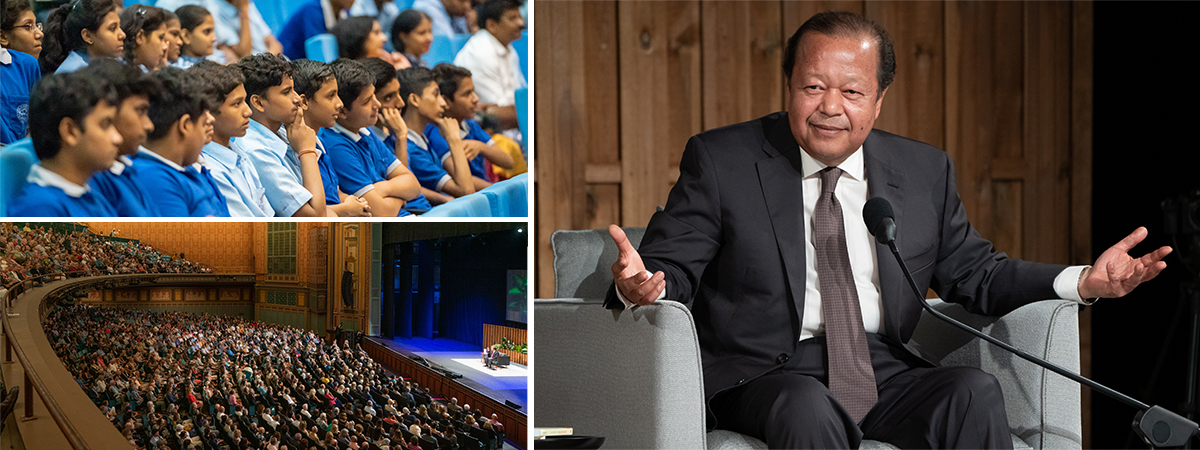

- Prem Rawat

00:06:05

How the Seed Survives

Video

Duration : 00:06:05

How does the seed survive in the desert? It made an investment. This is your pos...

00:06:05

How the Seed Survives

Video

Duration : 00:06:05

How does the seed survive in the desert? It made an investment. This is your pos...

What’s going to cause the divorce between the husband and wife? Expectations. What’s going to cause you to become angry with your own child? Expectations. And you have expectations of everything in this world.

I’m not saying that’s good or bad; that’s up to you. Certainly I have expectations too. I even have expectations of my dogs. Sometimes—and they’re two little Pomeranians, and theydon’t like anybody coming into the courtyard. Like, they’re, it’s theirs.

And sometimes I’ll sneak in, and they don’t know it’s me, and they’ll start barking. And then I’ll say, “What? What?” And then they get very, very embarrassed.

So, it’s not like, one way or the other way, “Should you have expectations; shouldn’t....” That’s not the point. But there is a state of being in which you are free, in which you are happy with yourself without the approval or disapproval of other people, where you recognize truly who you are is not this desert, but the seeds that lie buried in thatdesert.

My friends, the story is not about the desert. It’s going to look like the desert—the desert is going to look like the desert for a lot longer period than the blooming; the blooming is only going to last a few days. Understood, right? It only does—it just lasts a few days and then, ptchk! gone.

How does that seed survive in the desert? It had to work on it. It made an investment. It could be somewhere else where it rains a lot. But it didn’t; it went for the desert, in its uniqueness. This is the possibility; this is your strength! This is what can happen—only if you are willing to invest in it.

- Prem Rawat

00:16:50

Dream Within a Dream

Video

Duration : 00:16:50

Whenever this wisdom was passed to people, it would be in sync with the time, wo...

00:16:50

Dream Within a Dream

Video

Duration : 00:16:50

Whenever this wisdom was passed to people, it would be in sync with the time, wo...

One of my favorite stories that I have heard since I was a little kid—my father used to tell it—was, there was this king. And one day, this king was attacked, except this attack happened when he was sleeping.

So he’s lying in his bed, and he’s dreaming that he has been attacked, and that he has lost his kingdom; he lost the fight. And the winning king has given orders that he be executed—and he’s running through the forest to save his life.

He finally finds himself in the forest, and he’s hungry. He’s cold; he’s hungry. He finds a hut. In the hut there is an old lady. He knocks on the door, and he says to the old lady, “Can I have something to eat?” She goes, “I just finished making my food, and I have eaten it. But I do have a little bit of lentils left, and a little bit of rice, uncooked. Here it is. Cook for yourself, and eat and be satisfied.”

The king goes out, finds the wood—it has been raining and the wood is all wet. He starts a fire, and the fire is getting into his eyes. And it’s very difficult to start the fire, but he somehow manages to start the fire; he puts the pot on the fire. He puts the dahl, the lentils, the rice, a little bit of salt—cooks himself what is called a kitchari. If you’re from Scotland, a kedgeree—but it’s the same thing.

It’s too hot for him to eat, so he puts it on a leaf to cool down. Two bulls come by, fighting, and he has to move away. And they take what he has made, and stamp, stamp all over it, and mix it in the mud.

The pain of this defeat, losing the war, losing his kingdom, hunger, being in the forest—just imagine, that’s a nightmare! He’s having a nightmare, right? That’s the problem with nightmares; when you’re having them, you don’t know you’re having a nightmare. It seems so real.

And he starts crying. And when he starts crying, he’s crying for real. Not just in his dream; he’s actually crying, and that wakes him up. And he opens his eyes, and in the dim light of his room, lit by little lamps, he sees the magnificent bed, embroidered curtains. Gold is flickering from the little light of the lamps at night.

He can see the outline of his soldiers, standing their guard with spears, as their uniform is glistening from the little light from the lamps. He feels around him, and he’s lying on the softest possible bed he can imagine, with velvet pillows.

At that moment, a question strikes him. And the brilliance of this story is just this question that strikes him—which doesn’t strike us. That whoever wrote this story, whoever came up with this story....

See, well, you hear many, many stories—at least from me. And each one of the stories has a pivotal point, this one point that the author, the teller is trying to convey to you, that is the message of the story, that is the reality of the story. Now, it may not happen with Dirty Harry—that’s Clint Eastwood’s movie—it may not have that pivoting point of “something to tell.”

But these deep stories, which were truly a way to convey wisdom to people, to the masses who would hear it.... And people would go from cities to city, to village to village, and tell these stories, and this was people’s entertainment—how sweet that time must have been.

Before Ved Vyas—the person who wrote Mahabharat—the rishis and the many, many ashrams that existed, and many teachers that existed, had the knowledge, had the knowledge of what was eventually put in the vedas. But they refused to write it.

Writing existed, and means for writing existed. But they refused to write it. Do you know why? Because they knew that if it was ever written, it no longer would be synced with time.

That whenever this wisdom was passed to people, it would be in sync with the time. What would come out would be understood by the people of that time, would be current for those people of the time, would be accepted by those people of the time. It…they would be used by the people of the time.

The downside of it was, that as rivers shifted—because India was still moving north, and this is a reality of it; India is still moving around, and then the rivers are going, “Not here. Not any more.” And people have set up their ashram....

Because, one of the most—see, the…one of the most important things was water. And in those days, cities or villages or whatever was done, it was, “Make sure the water is available.” Because if you had the water, you could grow crops. And, of course, without water, no life.

Not like today, where there are these cities and there is no water. There is a—I saw a documentary of a city in California; there’s no water. And every ounce of water, for the toilet, for the sink, for brushing the teeth, is shipped in by trucks. And you don’t want to go there—because they conserve their water; they don’t take showers.

Anyhow, that something remains current. And here is the pivotal point of that story.

So, he wakes up. He looks around; he sees he’s still a king. Soldiers.... I already described everything pretty well, right? The question he asks himself: “Is this a dream? Or was that a dream,” where he’s hungry? He has questioned both! What would you do?

Oh, you know, instruments of truth, who can detect truth just like that—“Is there something black on my nose?” “No.”

You see, you know, have you seen mechanics? Car mechanics? Sometimes they will have a big line right here, and they don’t know. They’re going around like, “No, there’s nothing there.” To them, that’s the truth. The truth to you would then be, “Oh, no, no, look, look at your face.”

That’s not the truth either; that’s not the truth either, and he’s asking himself a question, “Which one was the dream?” Would we have the gall to ask that question, “Which one is a dream? Was our nightmare real—and what we are seeing now is real? And which one is a dream? Which one is the nightmare and which one is the reality?”

So, anyway, the story goes on; he makes a declaration, “Please, somebody answer my question.” People come out; he’s getting BS answers like he would today—stupid answers.

“You know, according to your astrology sign, that was just a nightmare, king. This is what’s real. Your destined to be the king; there’s nobody born who can defeat you, bla-bla-bla-bla-bla.” And he’s not buying it; he’s not convinced. He’s been touched by that dream so hard, he really wants to know which one is real.

That, there’s nothing to stop for him dreaming. That he has made a declaration—that he woke up and found that he’s still a king, when he’s maybe lying on some floor in the jungle, hungry and wet.

And finally, as—and so he keeps upping the ante, you know? It’s like, “Okay, whoever answers it can have this, can have this, can have this,” and it just kept escalating, escalating, escalating, and he finally gets down to it, and he goes, “Okay, I’ll give half of my kingdom to whoever answers my question.”

Everybody tried; everybody failed. Finally this person, Ashtabakr—and he was deformed! So, he comes; he sits down. And everybody starts laughing.

And the first thing Ashtabakr says is, “How come you have called me, how come you have invited me, O King, to the company of leather-workers?” In India, that’s an insult, by the way. That’s a low-down task, to work with the leather. “Chamar.”

Everybody hears the word “chamar” in his gathering, and they are like, “How dare you call these learned people ‘chamar’?” He goes, “They look at my skin—they look at my skin, and they’re laughing. They don’t know what I have in here, and they don’t know my knowledge. So obviously, they deal in skin.”

The king goes, “Okay, this, this sounds promising.” And here comes the answer—the second twist, the untangling—so, the tangling is, “Which one is real?” And the untangling, here it comes.

The untangling is, “O King, both are dreams.” Right? “Both are dreams. What you dreamt being in the jungle, being hungry was definitely a dream. But what you see with your eyes open, my king, is also a dream.” Tellers of truth, figure that one out. Both are—both are just a dream?

It is the easiest thing to forget: “This is a dream.” Because you were so deep into this dream, that it doesn’t seem like a dream. And there’s only one solution to this problem—only one. Only one—to be reminded again and again and again and again and again, “It’s only a bloody dream; it’s only a bloody dream; it’s only a bloody dream.”

And of course, that’s what sets forth the value for the Master. “It’s only a dream; it’s only a dream; it’s only a dream; it’s only”—and you’re like, “And no, it doesn’t look like a dream. It doesn’t look like a dream.” But isn’t it? “It is a dream; it is a dream; it is a dream; it is a dream; it is a dream.”

“Doesn’t seem like a dream; it doesn’t seem like a dream,” “Yeah, but it is a dream; it is a dream; it is a dream; it is a dream.”

Just like he said, Ashtabakr said, “That was a dream, and this is a dream. Don’t seek reality here. If you want to seek reality, seek reality in you, in that real place that you have which is not a dream.”

- Prem Rawat

00:07:51

Things Change

Video

Duration : 00:07:51

If you have ever looked at a sundial, what it’s really showing you is it’s const...

00:07:51

Things Change

Video

Duration : 00:07:51

If you have ever looked at a sundial, what it’s really showing you is it’s const...

When you were a baby, you didn’t have much awareness of change, and this and that. But you started going to school and things changed—where, all the people you really knew were the people that you came across every day—your mom, your dad—now all of a sudden there are all these other people.

And you start learning you have to interact with them, and you have to be submissive; you have to be assertive, and somebody comes along and take your book, and somebody might do something and do something and do something, and you have to be nice, and you have to be this, and you have to be that. Things change. It’s not a severe realization; it happens pretty gradually.

Then comes that time when now you can have a driver’s license—and you feel, like, some sense of accomplishment, “Now things have changed!” And these are all kind of, “nice change,” but then comes that other change; you realize, “Ah-huh, umm-hmm! There is a new smell in the air”—that you never smelt before. And the body is not performing the same way.

And there are so many people who want to hang onto their youth—when the body itself doesn’t want to hang onto it. “Done.” There is a big difference, my friends, in being healthy, staying healthy—and trying to look like who you are not. Do you get it? There’s a big difference.

Because, one is a presentation—of that which you are trying to hide, which is inevitable. It’s going to happen. It’s going to happen! Slowly, things are going to change, and this change has been afoot. This change started when you took your first breath. Not before that. When you took your first breath, this entire change started.

Now, I know everybody’s like, "Whoa, that's heavy stuff." It’s not heavy stuff; it’s nature. This is how it does it. It’s for everything. Trees will age. Even rocks. Mountains!

You look at some mountains and they are nice and soft—right? And you look at the other mountains and they’re sharp, and all, you know, edgy and...? You know what the—why? One is an old mountain; one is a new mountain. The new one hasn’t had the chance to get softened.

That’s neither good nor bad. It has nothing to do with it; it is just how it is.

I say to people; I say, "Do you know that somewhere on this planet Earth the sun is rising always? And it is setting always. This process of sunrise and sunset is continuous." It doesn’t feel like that to us, does it? We look out; "Oh, the sun is out, but, ah, let’s go, arrr-arrr-arrr...."

But if you have ever looked at a sundial, what it’s really showing you, is it’s constantly moving—slowly—but absolutely.

So is your life, so is your body, so is this time, so is all of this. It’s in a constant motion. You don’t want that. You want—you want to have a little "pause" button, get to that one nice point and go, “Tah-dah! I want to stay here.” But that’s not how it is.

So, in this change, is there any certainty? Because change can bring another element into it, which is uncertainty; you don’t know where you’re headed. "What does this change actually do?"

Well, there is a certainty. And the certainty is, your ability to enjoy will not diminish, even with age. Your ability to feel gratitude will not diminish, even with age. Your ability to be happy will not change, even with age. Your ability to have clarity in your life will not change, even with age—provided, provided you have made those things the core of your life.

- Prem Rawat

00:06:19

The Train of Time

Video

Duration : 00:06:19

Knowledge of the self is the most beautiful knowledge there is.

00:06:19

The Train of Time

Video

Duration : 00:06:19

Knowledge of the self is the most beautiful knowledge there is.

There are two walls. You came through one wall when you were born. Then you were going. You're going, going, going, going... You are, by the way, you're on the train of time. There is a train of time. You're on it. And it runs exactly at the same speed. It doesn't go any slower; it doesn't go any faster. It keeps running, it keeps running, it keeps running, and then it hits this other wall and then you disappear.

This is the fate of every single human being. One day you will be gone whether you like it or not. So whatever is happening is happening between these two walls.

Now a lot of people are sitting there going, "What's on the other side of the wall? What is on the other side of the wall?" There are 7.5 billion people approximately on the face of this earth and they don't know. There's been a few billion before you and they couldn't figure it out.

Aren't you fascinated? "What happens when you go on the other side of that wall?" You should be fascinated by what is on this side of the wall. Not that side of the wall! You're making a grave mistake if you're fascinated about what's on the other side of the wall but not this side of the wall. Because you are on this side of the wall. And this should be fascinating. "Wow! Life!" Life is about presence; death is about absence. You're fascinated by absence; you're not fascinated by presence.

When you were born, what did they look for? That you're a boy or a girl? Did somebody open your hand..."What is his future, what is his future?" No. The first thing they look for - breathing or not breathing. I have been there for the birth of my children. And at that moment when that baby comes out, it's not about a boy, a girl. It's about breathing, not breathing. And everybody in the room literally, literally is like “Huh!”

Waiting for that first "waaah" and as soon as that happens, that "waaah" and the breath begins. You have no idea when the first breath is taken. Oh, the miracle! My goodness, what a miracle it is. When that first breath is taken, this is the first time the body of the mother is told, "This baby is here. This baby is alive." And you know what happens? Slowly, the blood from the placenta that is flowing through the umbilical cord starts to wane away. Because up till this point the baby is only being sustained by the mother and no other means. And if it doesn't breathe on its own, it won't happen. But as soon as the baby starts breathing, the baby's color starts changing from blue to pink. What a miracle! What a miracle! Blue to pink. And then slowly the umbilical cord starts to stop sending; the placenta stops sending the blood to the baby. And a hormone is triggered inside the mother to start releasing the placenta from the womb. The baby is on its own.

"Why is he talking about breath?" Well, shouldn't I? It comes into me and it brings me the gift of life, and because I am alive, I can see you. Presence, absence. My choice. I need to make a choice. Who are you? Presence or absence? Are you your beliefs? Because if you do not know yourself, you're just beliefs. Absence, not presence.

When there's a possibility to know, you don't stay in beliefs. You come to knowledge. Knowledge of the self is the most beautiful knowledge there is.

- Prem Rawat

00:03:34

Buddha's Bowl

Video

Duration : 00:03:34

If we don’t accept this gift, it’s not ours. It just lies there, dormant.

00:03:34

Buddha's Bowl

Video

Duration : 00:03:34

If we don’t accept this gift, it’s not ours. It just lies there, dormant.

Tom Price: (host)

And here’s—this is my question. And then we’ll get to yours in a sec; don’t worry. Great indulgence for me to be able to ask Prem a question.

I love the analogy of opening a gift; I love this idea of a gift. But the thing I kept thinking when I was listening to you is, “Once you have opened that gift, how do you stop the gift from rewrapping itself up?”

Prem Rawat:

Well, that’s a valid question—except, all that time, you realize that the gift never opened itself; it took you to open it. So it will take you to rewrap it and close it. And, of course, you can always do that. So, a gift is a gift; and unless you accept it, it’s not a gift.

There is a story—I mean, this analogy is a little bit backwards, but I think it’ll make the point—where one time Buddha was walking with one of his disciples. And everybody in town was criticizing Buddha, saying, you know, “You’re no good; you don’t do this; you don’t do that....”

And so the disciple said, “Buddha, doesn’t that bother you, all these people saying all these nasty things about you, criticizing you?”

So when Buddha got back, he took his bowl—and his disciple was sitting there—and he took the bowl and he moved it. And he goes, “Whose bowl is it?” And the disciple said, “It’s your bowl.” So he moved it a little closer to the disciple and says, “Well, whose bowl is it?” He goes, “Yeah, it’s still your bowl.”

He kept doing that and asking him, “Whose bowl is it; whose bowl is it?” And the disciple kept saying, “It’s your bowl; it’s your bowl.” And then finally he took the bowl and he put it in the disciple’s lap and he said, “Now, whose bowl is it?” He goes, “It’s still your bowl.”

He says, “Exactly right! If I don’t accept this criticism, it’s not mine!”

And it’s the same thing—that if we don’t accept this gift, it’s not ours. And it just lies there dormant.

And we come into this world and then one day we have to go. And then we wonder—and this happens to way too many people—at the last minute, they’re going, “What, what did I do?” you know? And yet, that’s just not enough time to sort it elegantly out, the way you would like to have it done.

But now is the time—and now you are alive and you can do things—and you can waste your life. And the thing is, what’s amazing is that the life isn’t going to come back to you and say, “You’re wasting me.” It would be nice if it did: “Khow, pow, khow,” you know? But it doesn’t!

And the other beauty of it is that, whenever you decide to accept this gift, instantly it’ll become yours. So, it’s never too late! It doesn’t matter, you know, if you’re saying to yourself, “Well, yeah, well, I’m eighty-four. It’s too late for me.” And no, it’s not! Or it’s, or, somebody’s saying, “Oh, well, I’m too young.”

No! And, you can’t be too young; you can’t be too late with it; the day you accept it, it’s yours.